What would it be like to see like Rembrandt - to sense the gesture in all things, looking through the squalor and ugliness and finding a deeper, hard beauty in all that: what was that like? Can we let him suggest to us the penetrating gaze, the love of everything alive and being and moving?

Even if you’re listening to pounding music in headphones and everything is lit by street lights and neon signs and the subway rumbles underneath you?

Is Rembrandt’s gaze - 350 years old, pre-industrial, pre-electric, pre-mass-media - unrecoverable, anachronistic, irrelevant?

I ask myself this all the time.

There’s a saying in Torah study that if Moses were to come to a temple today he wouldn’t understand Torah, for he has missed out on 2500 years of commentary.

You have the amazing good luck to be a designer of today, right now.

When I went to NYU, my teachers were men and women of the theater of the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s. They taught about designing for a world that economically, technically and culturally doesn’t exist anymore - and yet their deeper lessons about design and life go through my head every day. Even if I turn their lessons on their heads.

For the next three years, remember this - keep it lodged in some protected part of your mind: It’s going to feel at times that we’re making you draw, see, and design our way, in some official, approved manner. But it’s really about leaping over and flying beyond. We’re here to help you surpass us, and to work in a world that no one knows yet is possible.

Camus said that no graduation ceremony is complete until the students consume the faculty.

I’ve been doing this design stuff professionally for coming up on 30 years and I’m good and smart and you should listen to everything I say - and I want you take everything I have, like a thief in the night, and misuse it for your own ends.

Your Mission

Be astonishing.

Have a great year!

Summer Drawing 2018

Saturday, August 25, 2018

Sunday, August 19, 2018

Fabric

Have you looked at the drawings of the great masters of the past as well as amazing contemporary artists and felt like they all had some secret understanding that, despite all your art classes and hours of smudgy charcoal, no one had ever told you?

You're right, they did all have an intrinsic idea behind their work which I am now going to reveal to you, before you've even started class, and you can all thank me later.

In the seminal book 'The Natural Way to Draw,' the great teacher Kimon Nicolaides says it this way:

We don't draw what something looks like; we draw what it is doing.

We draw the action, the forces and gestures of things. Gravity pulling down, energy thrusting up, action twisting and turning.

We draw the verb and not the noun.

An excellent subject to apply this is fabric, an active fluid material that shows the effects of force and action even in repose.

Every single designer needs to understand the qualities of fabric, what it does and why, and costume designers become complete experts on every seam and weave and thread. In the kit of symbols we learn to draw with, however, we don't really have workable marks for drawing fabric

We must always draw fabric by drawing the pull of gravity, what keeps the cloth from falling to the ground, and how does it twist and fold around forms. The dress, for example, that hangs from the shoulders and gathers across the chest and cascades down the back - it really helps to think in terms of active verbs that give life and energy to the forms of fabric. The dress is not just There - so much is happening!

Think of verbs that can describe fabric; here's 15 off the top of my head:

Fall

Cascade

Drape

Spiral

Flow

Buckle

Stretch

Burst

Tear

Gather

Bunch

Pucker

Pinch

Drop

Twist

Can you add any?

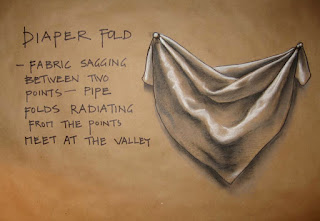

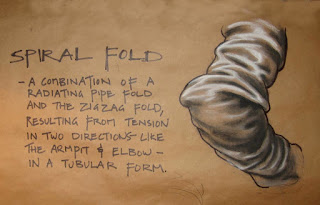

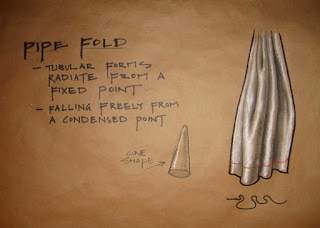

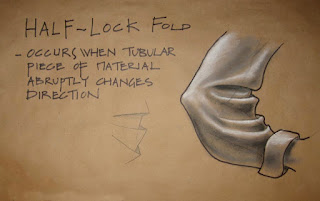

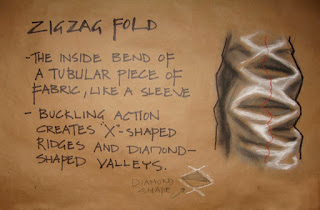

George Bridgman, teaching at the Art Student's League a hundred years ago, broke down the different effects of fabric into the following five categories:

Now, even if fabric often acts like it never read any of Bridgman's books, these are a really helpful guide, and repay study.

Your Mission

Take a piece of fabric, drape it over a chair, and draw it in pencil. Simple as that!

It may be a dress, a sheet, a towel, 2 yards of China silk - it's up to you. It should be a solid color without any pattern, and it probably should be a lighter tone for simplicity's sake. Convey the sense of the fabric's fall to the ground being impeded by the hard form of the chair. Use shading simply and clearly. Use line weight to make the overall form clear, and don't let the lines of folds and wrinkles overwhelm the drawing - big forms first, details within.

And show me that rather than just doing an exercise, you are opening yourself to the miracle of actuality before your very eyes, the joy of perception! As Blake said, all movements and all sights contain the seed of ecstasy!

Fabric Study, Leonardo Da Vinci

Ox Gall ink wash on prepared paper,

heightened with lead white

circa 1470, Louvre

Sunday, August 12, 2018

Reporting

This is really about how drawing works for designers. There are herds of drawing classes for the rest of humanity who are sadly not designers, where centuries of graphic tradition are heaped on people with no other point than to draw nice drawings. But we designers draw the way elephants use their trunks – it’s how we interact with the world, and how we communicate (so please picture an elephant trumpeting with his or her trunk when you are drawing).

What makes a drawing a designer’s drawing? The point is not a display of skill or even to make a beautiful drawing (though both things are useful, in the background), but communicating. Design drawings are often covered in notes, the words and images combining to tell as much as possible - a costume sketch will note the silk trim and the distressed leather boots and in which act this character wears this, while set sketches note the glossy paint finish and where the wall moves between acts I and II, and so on.

It is also about communicating with ourselves - we can argue that we don’t know how we see something until we draw it.

The world is filled to bursting with surprising things, and it’s brilliant to keep a sketchbook to try to pin down fleeting appearances, and try to work out what the hell is happening here. Some of the notes and sketches could later be extremely useful, as you use a scribbled space or person as the inspiration for a design, but many will be just for interest, to keep your eyes open and your drawing muscles limber.

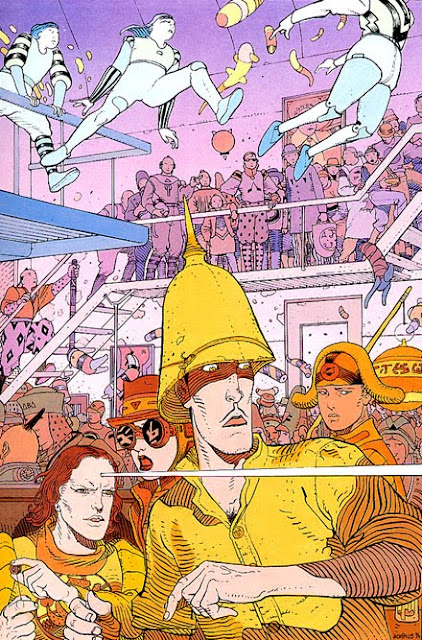

Here are examples of pages from my own sketchbook, including recent times in airports. I’m looking at people and trying to figure out what’s going on – recording appearance but also asking what their relationships are, what’s propelling them.

What makes a drawing a designer’s drawing? The point is not a display of skill or even to make a beautiful drawing (though both things are useful, in the background), but communicating. Design drawings are often covered in notes, the words and images combining to tell as much as possible - a costume sketch will note the silk trim and the distressed leather boots and in which act this character wears this, while set sketches note the glossy paint finish and where the wall moves between acts I and II, and so on.

It is also about communicating with ourselves - we can argue that we don’t know how we see something until we draw it.

The world is filled to bursting with surprising things, and it’s brilliant to keep a sketchbook to try to pin down fleeting appearances, and try to work out what the hell is happening here. Some of the notes and sketches could later be extremely useful, as you use a scribbled space or person as the inspiration for a design, but many will be just for interest, to keep your eyes open and your drawing muscles limber.

Here are examples of pages from my own sketchbook, including recent times in airports. I’m looking at people and trying to figure out what’s going on – recording appearance but also asking what their relationships are, what’s propelling them.

Edward Hopper’s sketchbooks are filled with drawings that are so clearly for him, showing as much as he can with the pencil – form and shade – and using notes to record color and texture impressions, and reminders of the quality of light, the feeling of the shadows, etc.

James Jean is a contemporary illustrator many of you may know of, who draws with an enviable freedom. Many of his sketchbooks are sold in reproduction, and many are online, like here.

I mean, yes, you can snap a picture of things around you with your iPhone, but you draw to discover as much as to record visual events and ideas. Putting ideas through your eye-to-hand-to-brain feedback loop makes them yours, marks them with your thought process.

I still have my own sketchbooks from my time at NYU, 30 years ago. They’re there on a shelf with many more sketchbooks, filled with big and small ideas, all of them completely mine. By opening yourself to the strangeness and banality and beauty and boredom of the world, you can get a sense of who you are as an artist.

Your Mission

Grab your sketchbook, head to the coffee shop, and draw the people and the space. Or a bar or a park or a waiting room or wherever – if you are traveling, airports are perfect spaces to record humanity. Note details. Wildly speculate about whom these people are, what is happening in this space.

What are people doing or wearing that shows that it’s 2018? What signals are people putting out to the world? What signals are intentional, which are unintentional? You are doing research for the big picture.

Your Mission

Grab your sketchbook, head to the coffee shop, and draw the people and the space. Or a bar or a park or a waiting room or wherever – if you are traveling, airports are perfect spaces to record humanity. Note details. Wildly speculate about whom these people are, what is happening in this space.

What are people doing or wearing that shows that it’s 2018? What signals are people putting out to the world? What signals are intentional, which are unintentional? You are doing research for the big picture.

Thursday, August 2, 2018

The Line

The summer advances, the fireflies are fewer, the air conditioner needs a rest. I hope everyone is mixing some of those fantastic summer things in with all your graduate school preparations, like eating frozen bananas while floating down a river in an inner tube, or whatever your version of a fantastic summertime thing is.

This week's mission is simple and sweet, an important idea we'll conquer easily.

Drawing is a complex activity, there's no doubt about it - when your pencil is moving around the paper there are so many things to consider, keep straight, balance, and it can always be better. Many of the aspects of drawing we're looking at quickly in this summer course are massive ideas - like Proportion, from week 2 - that we could spend months profitably turning this way and that. There are several ideas, though, that we can raise, consider for a week, then stash away for when it's useful later.

Lines

We want our lines to be clear, responsive, and varied as they describe different surfaces, textures, hard and soft passages, etc. A drawing with one unchanging line doesn't pull us in - lines that have contrast interest us, helping describe the variety within the subject.

Line Weight it one of those ideas that we can absorb quickly. We have several examples here of master draftsmen from various times. Moebius, the pen name of the French cartoonist Jean Giraud, who died in 2012, was a comic book artist (and my personal hero) with a beautiful free flowing line that he could vary so subtly - here, thicker lines brings objects into the foreground, while thinner lines are for details and distant objects.

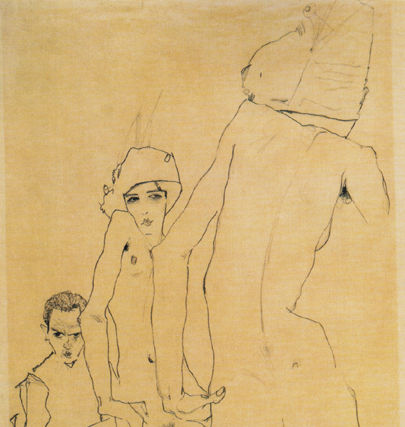

Egon Schiele had a profound sense of line, and a profound sense of anatomy, and it is remarkable to see what he conveyed just with his responsive, varied outline, with really minimal lines within the form.

Rembrandt provides the most masterful use of varied line, here with quick brushstrokes that you can almost count, but his lines and tones are so varied, accomplishing so many things - I never get tired of looking at this drawing.

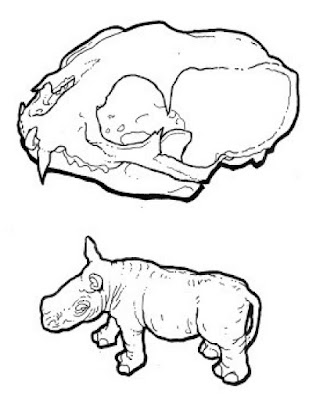

When I was a design student I had a teacher lay down the law for drawing costume renderings: your thickest line for the silhouette; your next thickest line for lines of tailoring; your thinnest line for wrinkles and texture. Boom boom boom. I learned it that way, and while I happily vary it and change it around, the clarity this approach gives is undeniable. Here are some sketches done at the American Museum of Natural History, with a nice thick silhouette and detailed passages within the form with a thinner line.

Your Mission

You may use two pens, like a Sharpie and a Mikron pen, with contrasting line widths, or you could use a pencil for this assignment. Choose a nice subject, with an interesting silhouette and interesting passages within. Some ideas:

A pile of shoes

A cauliflower

A stack of various books

A dress tossed on the floor

Six asparagus in a pile

You could also try this on the self-portrait you did earlier.

Use your imagination and surprise and charm me. Do a quick quick sketch to establish the overall form, and then draw a good strong, descriptive silhouette. Then map out important details within - what's the least you can get away with and still have a drawing that's fun to look at? Don't worry about shading, this is purely an exercise in line (seriously - look me in the eyes - no shading). Make your lines definite and continuous - we're saying good bye to the wispy, sketchy line.

Sunday, July 29, 2018

Light and Shade

Drawing, in the Western art tradition, is an agreed upon lie: to make marks on the surface of a piece of paper that create the illusion of depth. You could, very easily, list 40 other things drawing can be about, but our concern is representational drawing, and it has a particular vocabulary of marks and tones that we accept as describing three dimensions.

Degas said we have no natural sense of form - we must teach ourselves to perceive it consciously. I was startled when I first read that in Degas's letters, but with time I've become convinced he was right (and he was, after all, Degas). As we've said before here, we have to learn to consciously master the perceptions we register unconsciously.

Here is a circle.

There are really 5 ways of convincing the viewer that a circle drawn on paper is in fact a sphere:

1) Cross Contour - we can describe the round surface with lines, like the lines of latitude and longitude on a globe.

2) Chiaroscuro - where tonal contrast gives the impression of a light source that illuminates one part of a form more directly, while other parts fall away into shadow - we will look at this in greater detail below.

3) Overlap (also called 'Occlusion’) - one thing apparently obscuring another indicates one object is closer to the viewer than the other, and hence in space.

4) Aerial Perspective - the effect of atmosphere on objects of greater distance - a blurring of detail and contrast, and, in color, a shifting towards the blue that shows the effects of the intervening water molecules in the air.

5) Repetition of Form - the large form suggests a foreground, and the small from suggests another object the same size but in the distance.

We're going to look at the first two ideas this week. The idea of a contour line that runs over the surface of a thing, describing the topography, is a very powerful way to understand the form. One of the reasons it's so fascinating to draw in this way is that it's immediately apparent when it's wrong - and hence is an excellent learning tool. Students, however, often tell me it 'messes up' their drawing - But not us! We will be bold and explore.

Chiaroscuro, which literally means 'light-dark,' is a much fancier way of saying 'shading' - revealing the form through tones that mimic the effect of light and shadow on a form.

Here are some thoughts:

We try to simplify the light source in our drawings - in life light bounces around everywhere, and in our modern lives we are often in environments with dozens of light sources. Here we assume a single light source, from the upper left, a traditional light direction in Western art. Light travels in straight lines until it meets an object, where light rays are either absorbed or bounce off.

On the sphere below, you can see how we see the light as it's bouncing towards us at different angles. The highlight is that spot where the light source bounces off the object directly into our eyes - the brightest spot. As the form turns away from the light source, less and less light finds its way to our eyes. If the form turns smoothly away from the light source - like a sphere - the lights subtly shades into a darker value. If it turns abruptly away, like the right angle of a cube, the tonal shift is likewise abrupt.

So here's a rule: when there's a change of plane, there is a change of tonal value.

Note the parts of the sphere here:

The Highlight, which we've discussed - the brightest point.

Twilight - where the form has turned away from the light to the point where the light just grazes the form. This is an important portion of the drawing, for it is here that we find texture expressed - and, in a color painting, this is where a red apple, say, is really red.

The Shadow Core - the darkest point of the form, where the shape has turned fully away from the light source, but is not illuminated by the reflected light

Reflected light - Light bouncing up from another surface - in this case the surface the sphere sits on - casting light on the portion of the form that is essentially on the opposite side from the highlight. The reflected light, properly understood, is really what gives the sense of a fully dimensional form.

Cast Shadow - The shape formed by the interruption of a light by an object, seen as a shade on another surface. Note that cast shadows generally have hard edges. Often in figure drawing classes teachers want the students to deemphasize cast shadows, for these hard edges can interfere with our understanding the body as a series of smooth forms. (But for costume renderings - excuse me if I get ahead of myself here - cast shadows are extremely important and often neglected by students - the shadow cast by the hem is as much apart of the design as the hem itself).

One last thing to consider: let's imagine ten tones from white to black - if you've had art classes you likely have had to create these tones in pencil, watercolor, oil paint, etc. Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, the Neoclassical painter, had his students mix 400 shades of gray between absolute white and absolute black - and then do a painting of the figure that used all 400 shades. We will not require that of you. But begin to look at things and see if you can separate ten shades - that is 30%, that is 80% gray, etc.

An important point: no longer can your shading be scribbly, which is how I would describe many of your drawings. To draw tonally means that we shouldn't be aware of the pencil marks, for lines that are too regular and parallel or seem random and scribbly sit too much on the surface of the paper and destroy the illusion of depth that is our goal.

A nice drawing has a pleasing balance of tone - it's up to you to decide what that balance is. But push things - make darks dark, and grays that have a full range.

Your Mission

It's summer and things are growing! And in the interest of promoting your health, I want you to buy some nice fruits and vegetables and draw them! (I worked as an cookbook illustrator when I was first out of college, and I loved that period when I always had little tableaux of vegetables on my drawing table).

Do a lovely tonal study of the fruit or vegetable sitting on a surface, with a beautiful sense of chiaroscuro. Keep the tones simple and clear.

Have fun. Don't fret. Feel free to eat your still life subject when you've completed the drawing. And here, for inspiration, are some still lives of things healthy and not, by my teacher, Wayne Thiebaud. He said that when you are at a loss for something to do, you can always assemble a group of things you like on a table, take some paper and a pencil, and be as honest as you can.

Sunday, July 22, 2018

Proportion

We understand things only in relation to other

things. I'm tall when I stand next to my wife, I'm short when I stand next to

Kareem Abdul-Jabber (which I did once). We need a frame of reference to

place everything within, and the human body - ourselves - is the obvious

starting point.

As designers we get to be experts on proportion

and how parts relate to the whole. We should be experts on how we fit into the

world around us.

We will look at the proportions of the human

figure, looking at what in Western art are agreed upon 'ideal' proportions, and

how, even if none of us conform to the ideal, it can be a useful starting

point.

I imagine everyone has seen Da Vinci's drawing

of Vitruvian Man, a man encompassed in a square and circle. This comes from the

Roman writer Vitruvius, whose 'Ten Books of Architecture' are the only

classical writings on architecture to come down to us (go Google him now!). He

tells us:

"For if a man be placed flat on his back,

with his hands and feet extended, and a pair of compasses centered at his

navel, the fingers and toes of his two hands and feet will touch the circumference

of a circle described therefrom. And just as the human body yields a circular

outline, so too a square figure may be found from it. For if we measure the

distance from the soles of the feet to the top of the head, and then apply that

measure to the outstretched arms, the breadth will be found to be the same as

the height, as in the case of plane surfaces which are perfectly square."

His work did not survive Roman times with its

original illustrations intact, and there were several attempts to work a

plausible image of Vitruvius's ideal before Da Vinci's happy drawing. It shows

how our height is, in theory, the same as the width of our out stretched arms,

fingertip to fingertip.

I will confess that this doesn't work for me:

the distance of my outstretched arms is shorter than my height - one of many

ways I fail to correspond to the ideal.

Vitruvius also tells us "the head from the

chin to the crown is an eighth [of the height of the body]" and this has

been used as an ideal proportion in Classical times, to be rediscovered in the

Renaissance, and taught in art schools to this day.

Is anyone 8 heads high? Look at people around

you - try employing the method I illustrate here. Are there people 7 heads

high? 7 1/2? 6?

Andrew Loomis here illustrates the useful

landmarks of the body and the accepted proportions. The crotch is the mid point

of the body - the length of the legs is equal to the torso and head. The lower

legs are equal to the upper legs, with the knee at the halfway point - likewise

the upper arm and lower arm are equal, with the elbow as the midpoint.

[Feel free to be slightly offended by Loomis's

definitions of ideal proportions - these are from his 'Figure Drawing For

All It's Worth,' published in 1943, and carriedthe attitudes of its times. But

he is an excellent teacher - 'Figure Drawing For All It's Worth' has been

recently republished and might be a good book to have)

Try measuring yourself against these

proportions. How many heads high are you? Compare your wingspan to your height.

Where do the major landmarks of the body fall on you?

(I also include this one just because it’s so

trippy. A woman, in this example, is 7 ½ heads high)

Your Mission

Measure yourself thoroughly and accurately,

head to toe. Measure an object (a chair, a rhinoceros, what have you). Draw

yourself next to the object, calling out dimensions, midpoints, and

correspondences between you and the object. You may work in the metric system

if that's what you are used to, but now may be a good time to begin working in

feet and inches. And take a good look at Andrew Loomis's illustrated

proportions, for you will, eventually, be called upon to memorize them - but in

the meantime, see how you can make this assignment fun for yourself. Send to me

by Saturday, July 28.

Onwards and upwards!

Chris

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)